“The title is really ‘Eden’?” I asked, shaking my head. “That’s both uncreative and presumptuous.”

Then I read it—the poem by Javen Tanner in Fire in the Pasture. And I nodded.

From what I understood, the poem describes a secret meeting and sharing of fruit between the speaker and his lover in a garden. While it’s apparently a modern tale, Tanner makes several references to the story of Adam and Eve throughout the poem. He seems to feel that he and his lover are mirroring Adam and Eve’s experiences in and after the Garden of Eden.

My basic opinion about what makes poetry “good” is how much or how differently it makes me feel. And I generally have a hard time expressing these feelings in the usual terms. Such is the case with “Eden.” Its Biblical imagery brought a sense of the epic, spiritual, and inevitable. The slight differences between the Bible quotations and the poem’s paraphrases brought depth. And Tanner’s diction brought intimacy.

The diction in particular caught me. For one thing, his use of the word “proxies” in the first line was spot on. I had to look up the word “nomenclature” from the third stanza, and I’m still not sure I know exactly what Tanner meant by it. But that’s part of poetry’s art, too, I think. Perhaps the only word I didn’t like was the word “sick” to describe the air, but it admittedly fit the theme of its surrounding lines.

And the poem’s final stanza describing the fruit—a peach—and the woman’s heart. . . . Again, I’m not sure if I “get” the lines completely, but they’re perfect:

delicious and desirable.

See how it beats and bleeds,

how it breaks to heal itself.

These lines feel like life. And love. And it made me wonder how breaking heals. But I suppose that’s exactly the point, isn’t it?

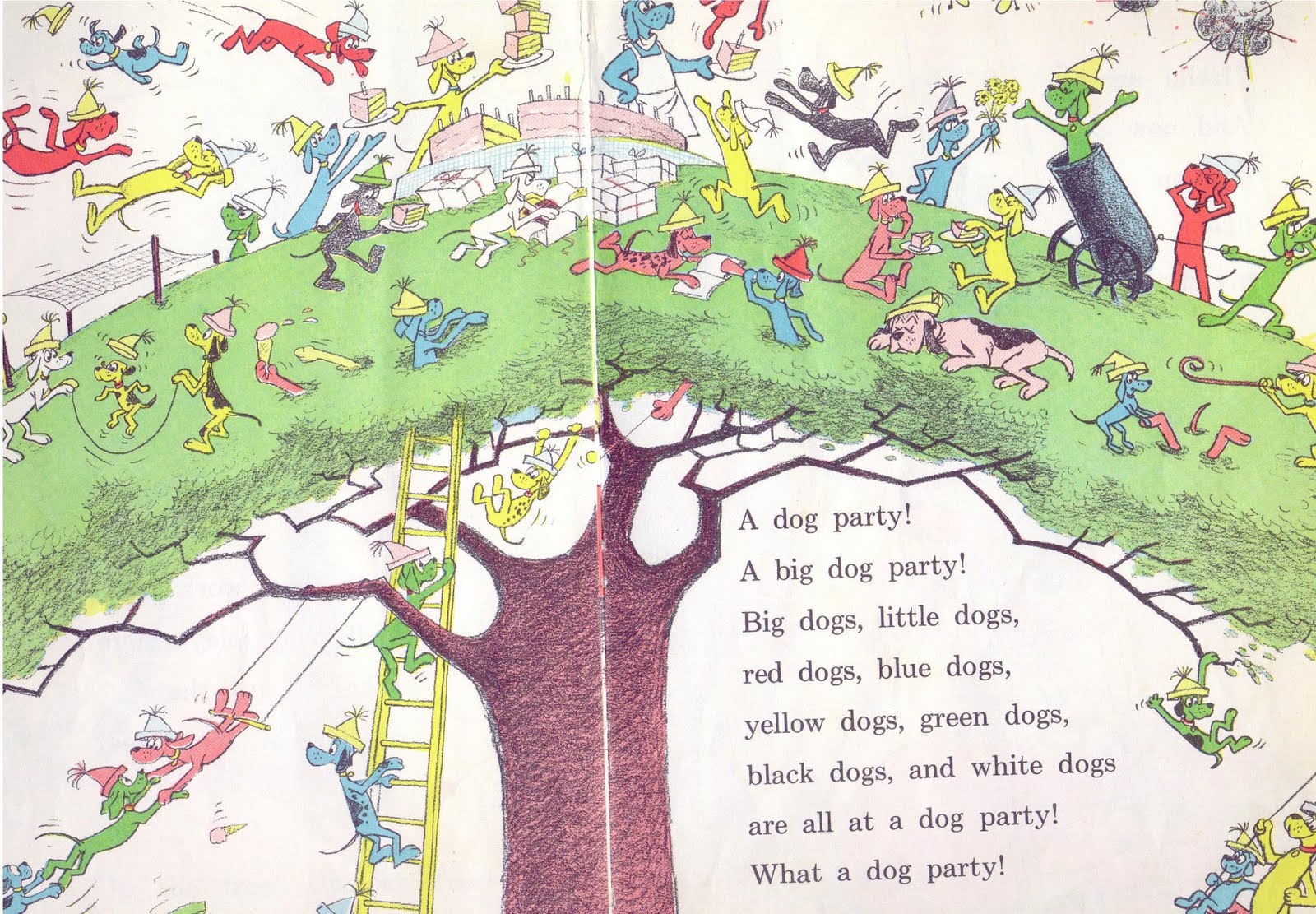

Another, being to start over again. Life is a cycle with childhood, adolescence, adulthood- which essentially starts over with each new generation. I hope my children will have the same child-like wonder in books that I did, and that I have the same adult-like wonder in children as Chadwick does.

Another, being to start over again. Life is a cycle with childhood, adolescence, adulthood- which essentially starts over with each new generation. I hope my children will have the same child-like wonder in books that I did, and that I have the same adult-like wonder in children as Chadwick does.